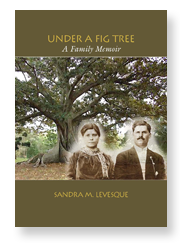

"The Women of "Little Randazzo"

By Sandy Levesque

|

The young wives who made the Atlantic crossing from Randazzo to Rutland in the early decades of the 20th century were country women, whose horizons in Sicily were even more limited than those of their adventurous husbands. Most had not gone to school for long, if at all. Rather, they were sent to the fields and vineyards where they worked alongside, and as hard as, men. They were also expected to help their mothers with wood-gathering, bread making, laundry, cheese and soap making until it was time for them to marry, raise children and nurse their own families and elderly parents through difficult times. With the promise of a better life in America, these sheltered women parted from their families, probably not fully comprehending that they would never see them, or Sicily, again. Such was the case with Antonia Maria Delpopolo Scafidi, who emigrated to Rutland in September 1920, with her husband, Francesco. She was twenty-two years old, married for six months, and in the first trimester of pregnancy for her first child. Once settled in "Little Randazzo", Antonia and the other women in the neighborhood rarely left their postage stamp parcels of home and garden. All of their energy was harnessed to caring for and feeding their families in the long-standing tradition of Sicilian women from the villages they left behind. Their standard issue wardrobe consisted of cotton print dresses hemmed at mid-calf, covered by calico bib aprons. During the day, while their husbands were at work, they ruled over the neighborhood—watching from behind parted curtains, kitchen gardens, and shady porches. Their telepathic network maintained an unspoken sense of order and daylight decorum—an informal Neighborhood Watch. In the summer they coaxed whatever vegetables they could from the strange Vermont soil, in neatly tended backyard gardens. They packed their root cellars with bushels and barrels of the harvest and filled the shelves with canning jars in a rainbow of colors to prepare for a season that did not exist on their Mediterranean island. Food was their passion, but their frugality is legendary. When it came to marking the special occasions of their family and community life, penny-pinching and practicality were put aside to indulge in the one culinary excess for which their homeland is celebrated—i dolce, its desserts. While Sicilian pastry recipes very from region to region, village to village, and even from family to family, they are all universally linked to an ancient legend, the celebration of a particular feast, or a saint's day. In "Little Randazzo", the pastries made their appearance at Easter and Christmas, but they also showed up by the bushel basket for Sicilian Club parties and picnics and on "cookie trays" (large mounds of assorted cookies) prepared for family weddings and reunions of all sorts. Antonia Scafidi's cookie trays included two staples—a spicy molasses cookie, the Mussetti, and its not too distant relative, the Anise Bar, sometimes referred to as White Mussetti. Both are examples of a localized dessert with similar ingredients to Neapolitan pastries associated with the Lenten season. The biscotti-shaped Mussetti, with its dry, dense, and chewy texture, is often dipped in coffee to soften. Both of the tasty cookies are baked in loaves, cooled, and sliced on the diagonal to create individual cookie bars. Unlike biscotti, they do not require a second baking to bring out their flavor. |